The Burundian government is intensifying its crackdown on the growing number of street children in key cities—particularly in the economic capital, Bujumbura—raising concerns among child rights advocates about the effectiveness and humanity of the approach.

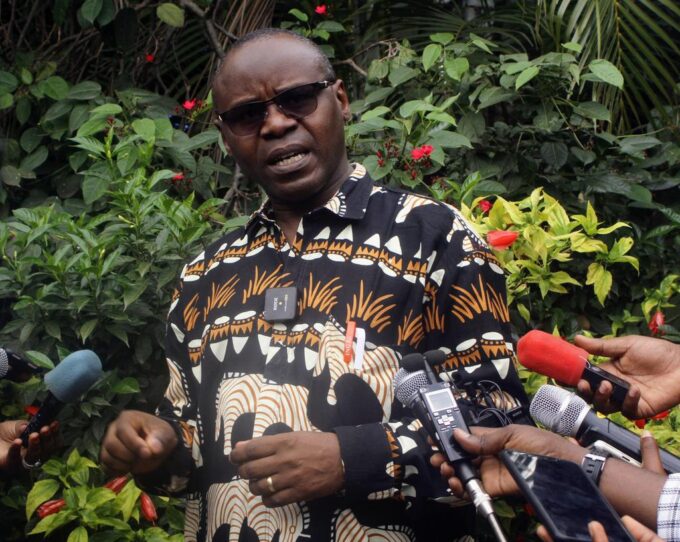

In a radio interview with Bonesha FM on Saturday, Ildephonse Majambere, spokesperson for the Ministry of National Solidarity, Social Affairs, Human Rights, and Gender, warned that legal action could soon be taken against parents who fail to fulfill their duties to their children.

“We are still trying to raise awareness among people,” said Majambere. “But imagine someone comes to a state center for help, gets assistance, and then goes back to the streets the next day. These repeated cycles end up looting state resources.”

Majambere accused some parents of willfully abandoning their children to the streets, placing the burden on state systems. “It becomes legitimate to say: ‘You are among the people looting the State,’ because you refuse to do your part,” he said, hinting that the government may begin holding such parents accountable through the justice system.

The official also pointed to Burundi’s penal code, which criminalizes begging, particularly when it becomes habitual. “Begging is an act punishable by law. If a prosecutor finds someone is using it as a livelihood, then there is no reason not to prosecute,” he warned.

Over the past year, police operations have intensified, with over 300 children rounded up and sent to rehabilitation centers, notably in Mishiha, Cankuzo in the country’s east. Yet many of these children continue to return to the streets of Bujumbura—Burundi’s economic capital—citing dire living conditions at the shelters.

Voices from the Streets

Jimmy Irankunda, 16, has spent most of his life on Bujumbura’s streets. He was among those recently sent to the Mishiha center. Speaking near the city’s central market, he described a bleak experience.

“We were fed the same food every day—plain rice and beans, no salt, no oil,” he said. “It was very cold, and there was nothing to do. I chose to escape.”

Similar stories are echoed by others. Fifteen-year-old Hekima Didier said children slept in tents and sometimes lost their mattresses to theft. “The food was so little, eight of us would share a small portion. We had no choice but to run away,” he said.

Thirteen-year-old Divin, who dropped out in primary school, added: “They would make us sit all day doing nothing, just to keep us off the streets. But it didn’t help. The place was terrible.”

Like many others, these children survive by begging or helping carry loads in markets. But their presence on the streets is now prompting tough talk from officials and increasing criticism from rights groups.

Rights Groups Call for Rethinking Strategy

David Ninganza, head of the children’s rights organization SOJPAE, warned that the government’s approach is flawed and risks making the problem worse.

“These children don’t just appear on the streets for no reason,” he told Breaking Burundi. “Each one has a story. Some are orphans, some face abuse, some were abandoned. The government’s reintegration strategy is poorly designed and backfires.”

Ninganza called for deeper investigations into the root causes of child homelessness and for more sustainable reintegration programs, including localized support and income-generating opportunities.

He gave the example of children from Nyanza-Lac, a fishing area in southern Burundi, arguing that localized solutions could work better. “Children need to be supported where they come from. Their needs are not the same. We must help them become self-reliant where they are reintegrated,” he said.

Vianney Ndayisaba, national coordinator of the rights group ALUCHOTO, supported the idea of holding parents accountable but emphasized the need for broader reforms.

“Some parents have no understanding of what it means to raise a child. We must ask: what happens when a child is returned home? Are they safe? Are they supported?” he asked.

Ndacayisaba referenced Article 30 of the Burundian Constitution, which outlines the shared responsibility between the state and parents in ensuring a child’s well-being and education. “A child is not raised on the street. A parent who willingly abandons their child should be held accountable,” he stressed.

Leave a comment