Child rights organizations in Burundi are sounding the alarm over a sharp increase in vulnerability to human trafficking following a sudden halt in U.S. foreign aid earlier this year. The executive order issued by President Donald Trump in early 2025 halted funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to international programs—leaving Burundi’s anti-trafficking efforts in disarray.

The impact has been immediate and severe. Civil society groups and government agencies that once played key roles in monitoring, prosecuting, and supporting victims of trafficking say critical activities have stalled. Children, already among the most at-risk populations, have been left without the protection they once received.

“We lost everything overnight,” said Yves Ishimwe, Program Director at the National Federation of Associations Engaged in the Domain of Childhood in Burundi (FENADEB). “Nearly all our child protection and counter-trafficking initiatives—direct assistance services to victims of trafficking and other child rights violations—were funded by USAID and the Department of State through the Office to monitor and combat TIP, often via UNICEF. That support is gone, and so are the programs.”

Fallout From “America First”

The aid suspension stems from the Trump administration’s sweeping “America First” policy, which seeks to limit international spending and redirect resources toward domestic priorities. Nearly 80% of USAID programs were affected, with African nations like Burundi among the hardest hit.

Before the executive order, USAID had funded a range of initiatives in Burundi, including awareness campaigns, parenting support, psychosocial care, legal assistance, and shelter for trafficking survivors. All of those services have now either stopped or been drastically scaled back.

“The government’s own programs haven’t been spared,” said Epitace Masumbuko, Chair of the National Task Force Against Human Trafficking and Head of Internal Security and Arms Control. “Ninety percent of our initiatives are stalled. The USAID suspension disrupted everything.”

In 2023, the government, in collaboration with various ministries and supported by international partners, had launched a five-year National Action Plan to combat human trafficking. The plan, estimated at $9 million, was structured around four pillars: prevention, protection, prosecution, and partnership.

But by year three, nearly all momentum had been lost.

Human Impact on the Ground

For frontline organizations like SOJPAE Burundi, a local nonprofit working with vulnerable children and youth, the consequences have been deeply personal. “We had to halt some programs and suspend staff salaries,” said David Ninganza, the group’s chairperson. “Our organization relied on indirect USAID funding through international partners. When their funds stopped, so did ours.”

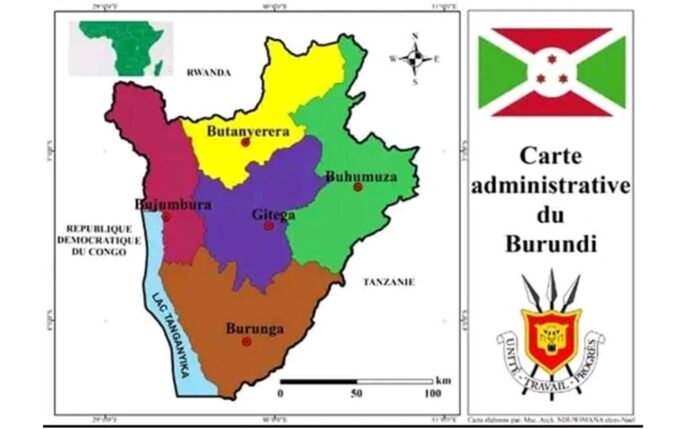

FENADEB, which has documented thousands of trafficking cases since 2011, was also forced to freeze nearly all of its operations. In 2024 alone, the organization identified more than 600 alleged trafficking victims—over 550 of them children. The vast majority were exploited in farming activities in neighboring Tanzania.

“All those services—legal help, medical care, emergency shelter—disappeared overnight,” Ishimwe said. “There’s no one to follow up with victims. Law enforcement officers arrest traffickers, but without a system in place, there’s nowhere to send the victims. Some perpetrators are released. It’s a complete breakdown.”

The ripple effects have also hit the government’s Anti-Trafficking Commission. Masumbuko noted that even though the structure remains, its ability to act has been crippled. “Some of the people we were supposed to help remain in crisis. We can’t move forward without resources.”

A Call for Domestic Action

Both civil society and government actors now urge the Burundian government to step up.

“These are Burundian children,” said Ishimwe. “It’s the state’s duty to protect them. We can’t continue depending entirely on foreign aid. We need a national budget that prioritizes these services.”

While the government has offered some emergency funds, experts say it is not nearly enough. FENADEB and the National Task Force are calling for the full implementation of Burundi’s 2014 anti-trafficking law and a reallocation of domestic resources to ensure continuity in vital services.

“Human trafficking doesn’t wait for budgets or elections,” Ishimwe stressed. “We must act now.”

Hope Amid Uncertainty

Despite the setbacks, organizations remain committed. Some staff have continued working without pay, and dialogue with stakeholders is ongoing.

“The work hasn’t stopped completely,” said Masumbuko. “But we’re far from where we should be. We’re still hoping that both international and domestic support will return.”

For now, however, the halt in U.S. aid has left a gaping hole in Burundi’s child protection systems. Without urgent intervention, years of progress in fighting human trafficking may be lost—and the country’s most vulnerable will continue to pay the highest price.

Child rights must be protected!