A total of 4,309 school dropouts, including 1,993 girls and 2,316 boys, have been reported in Kayanza Province during the first trimester of the ongoing school year, according to Burundi’s public broadcaster, RTNB. Juvenal Mbonihankuye, Provincial Director of Education, attributed these troubling figures to persistent poverty, ignorance about the value of education, and discouragement among students.

The communes most affected by dropouts are Kabarore, Matongo, Muhuta, and Gatara. Mbonihankuye highlighted the demotivation among students who see older peers remain unemployed despite holding diplomas, reinforcing the belief that education does not guarantee a better future. He described these dropouts as a “ticking time bomb,” warning of the long-term societal consequences if the crisis is not addressed.

To combat this issue, Mbonihankuye called on local administrators to enforce measures ensuring children stay in school and to penalize parents who prevent their children from returning. He also urged parents to instill a love of education in their children and discourage dropping out. Educational partners were asked to actively engage in mitigating the crisis, especially given that Kayanza Province recorded 16,169 cases of dropouts in the 2023-2024 academic year.

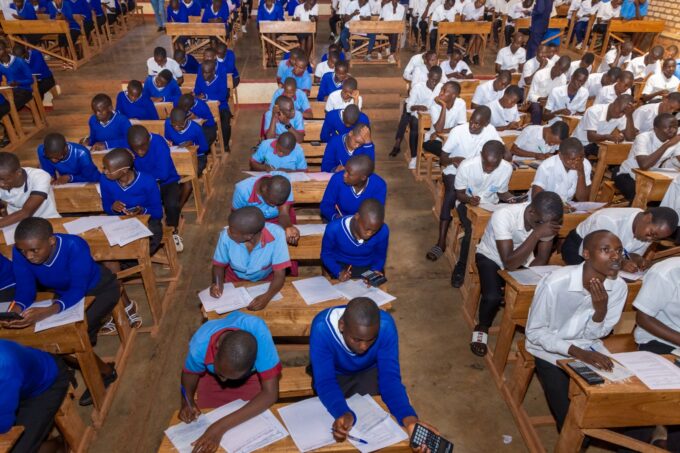

The dropout problem is not limited to Kayanza. This week, educational officials in Ruyigi eastern province expressed concern over students’ lack of interest in school despite widespread access to educational facilities as reported by the local magazine Jimbere. Jean Claude Gatoto, Director of Education in Bweru commune, said that of the 538 students who began first grade in 2016-2017, only 63 reached ninth grade. He lamented the declining number of university-level students from the area and urged parents to fully support their children, especially those preparing for national exams.

The broader societal perception that education no longer guarantees success is also fueling the dropout crisis. Many graduates, including those with university degrees, are forced to take low-paying jobs typically held by those with minimal education. In cities like Bujumbura, graduates often sell airtime, SIM cards, and phone accessories to cover basic needs, highlighting the mismatch between educational investments and job market realities.

“I dropped out of ninth grade, and I’m doing the same job as university graduates, including those with master’s degrees,” said a vendor at Onatel in downtown Bujumbura. “This shows that something is wrong in the country, and education is not as important as it used to be.”

As the country grapples with these challenges, stakeholders agree that urgent action is needed to restore confidence in the value of education and to address systemic barriers preventing students from completing their studies. Without such efforts, the growing number of dropouts threatens to undermine the nation’s development and exacerbate social inequalities.

Leave a comment