Burundi’s education sector is facing a deepening crisis as mounting challenges continue to undermine the quality of learning in schools and universities, according to PARCEM, a prominent civil society organization.

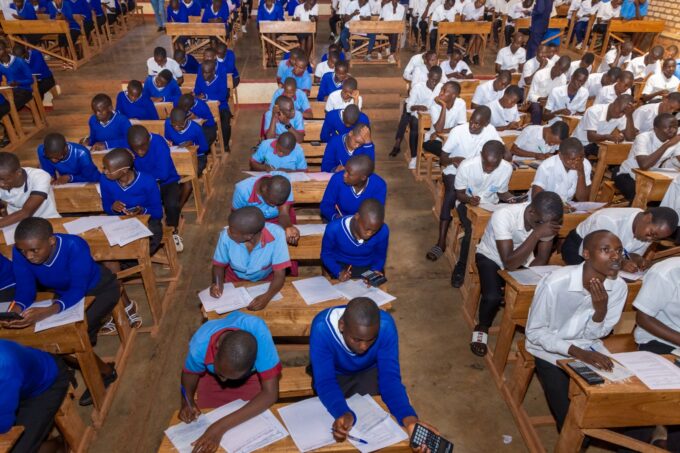

Speaking at a press conference on Monday, Faustin Ndikumana, the national director of the group, painted a grim picture of the country’s education system. He cited persistent shortages of school materials, overcrowded classrooms, low teacher morale, unqualified staff, and what he described as poorly designed reforms.

“The knowledge that children acquire in schools is alarming,” Ndikumana said. “When they come for internships, we are shocked — even those finishing university or doctoral programs. One can only feel pity.”

The director of PARCEM highlighted recurring problems such as the absence of basic resources like textbooks, desks, and adequate food in boarding schools. Teachers, meanwhile, have been leaving the profession in large numbers due to low salaries, poor working conditions, and retirement, with little or no replacements to fill the gaps.

Ndikumana also questioned the value of government spending on education.

“I wonder about the money being spent on education in this country — what is it really producing?” he asked.

Decline in Social Values and Political Interference

Beyond material shortages, Ndikumana raised concerns about a broader decline in moral values among Burundian youth, which he argued is eroding the quality of education itself. According to him, decisions in schools are often influenced by political interests, including during student evaluations.

He also denounced favoritism in the allocation of scholarships, claiming that some are diverted to unqualified students linked to government officials. “This is a disgrace for the country,” he said, adding: “If we are destroying our youth, what kind of leaders will Burundi have in the future? There is no possible vision for education if things remain this way.”

He also accused senior officials of making speeches that downplay the importance of learning, thereby discouraging students. While he did not name anyone directly, Révérien Ndikuriyo, secretary-general of the ruling CNDD-FDD party, has in recent years publicly dismissed the value of formal education saying it’s useless.

“What we study in Burundian schools is useless! Tell me, x² – 1 = (x – 1) × (x + 1), what does that help you with in Rugarama? Does it catch termites? No, let me ask you, does it catch termites?” he said during an event whose participants included young people , some of them were apparently students. In this context, “termites” was used metaphorically to mean money, implying that certain school lessons do not currently translate into practical financial gain.

Another growing concern, Ndikumana said, is the involvement of students in partisan political activities. He warned that using young people for political purposes risks derailing the country’s long-term development.

“The rightful place for children is in school, acquiring real knowledge,” he said. “The use of children in political activities must be reduced.If not addressed, this will derail the country’s development.”

Ndikumana’s remarks echo recent concerns raised by other civil society groups, which have highlighted similar issues, including ineffective reforms, declining teaching standards, and the lack of long-term vision for the education sector.

PARCEM’s leader has called for a comprehensive vision for education in Burundi, stressing that without serious reforms, the country risks producing generations unprepared for national development.

“If things remain this way, there is no possible vision for education,” he warned.

Leave a comment