Burundi’s economic capital Bujumbura continues to witness a growing influx of children living in the streets, despite repeated calls from rights groups and ongoing government interventions.

Street children who spoke to BREAKING BURUNDI during the commemoration of the International Day of the Rights of the Child on Thursday described dire living conditions that push them to drop out of school and migrate to urban areas.

“My aunt brought me here. I did not study. We moved from upcountry when schools had already started. I dropped out in fourth grade,” said 14-year-old Fleury Itangahageze, a native of Muramvya now living in Kinama neighborhood, northern Bujumbura.

Near the COTEBU market, Omar Ndayizeye, also 14, recounted how he was lured to the city by peers who promised job opportunities.

“I have both my mother and father. I came to Bujumbura after some friends told me we should go together to find work. I dropped out in third grade,” he said.

Others admitted that delinquency and stubbornness contributed to their decisions.

“I dropped out of school in fifth grade. It’s not that I lacked school materials—I just abandoned school,” said 15-year-old Emery Irakoze from Kamenge.

Most of the children, many under the age of 18, said they migrated from rural areas between April and June this year in search of better living conditions. They settle in commonly frequented urban areas, particularly markets. Some sell small goods such as sachets and dried fish, while others work as luggage porters.

While some sleep in drainage ditches along major roads, residents say street crime—particularly bag and phone snatching in the evenings—is on the rise.

Seven Thousand Children in the Streets, Few Resources Available

Earlier this week, Interior and Security Ministry spokesperson Pierre Nkurikiye raised concerns about the increasing number of street children, school dropouts, and early pregnancies—issues he linked to chronic underfunding.

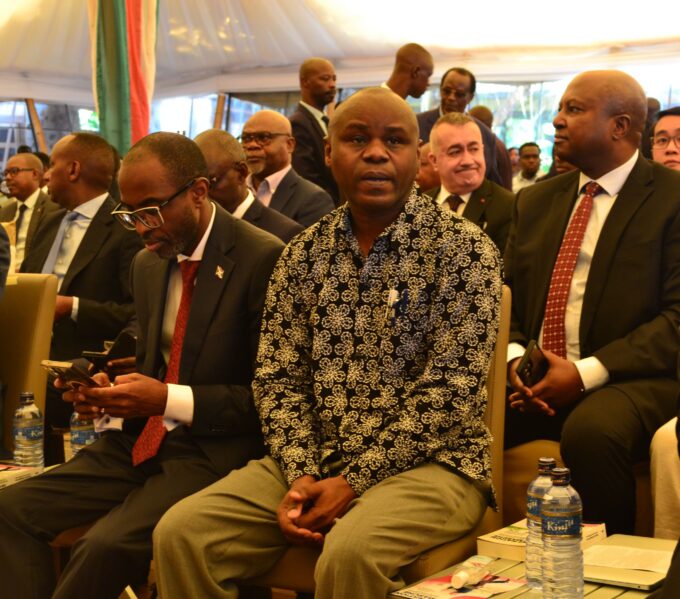

“When you look at the number of street children—today reaching nearly 7,000—and the more than 260,000 children who drop out of school every year, and the high number of students who become pregnant, you see a very concerning situation,” Nkurikiye said at a workshop on children’s rights.

He criticized the low budget allocated to child protection initiatives.

“At the same time, the funds allocated to child protection represent only 1.7% of the country’s annual expenditures,” he said. “Yet abuses committed against children affect nearly 89.6% of them. It is clear that the resources dedicated to child protection are still insufficient.”

Civil society also voiced concern. The National Observatory for the Fight Against Transnational Crime (ONLCT), a prominent child rights organization, condemned the rising numbers and cited additional challenges, including children not registered at civil registry office—making them vulnerable to trafficking.

“No country can claim to develop when faced with such a high number of street children, and when 15% of Burundian children are not registered at civil registry office,” the organization said in a statement issued Thursday.

Earlier this month, David Ninganza, head of the children’s rights organization SOJPAE, said the government’s approach remains flawed and risks worsening the crisis.

“These children don’t just appear on the streets for no reason,” he said. “Each one has a story. Some are orphans, some face abuse, some were abandoned. The government’s reintegration strategy is poorly designed and backfires.”

Past Government Measures

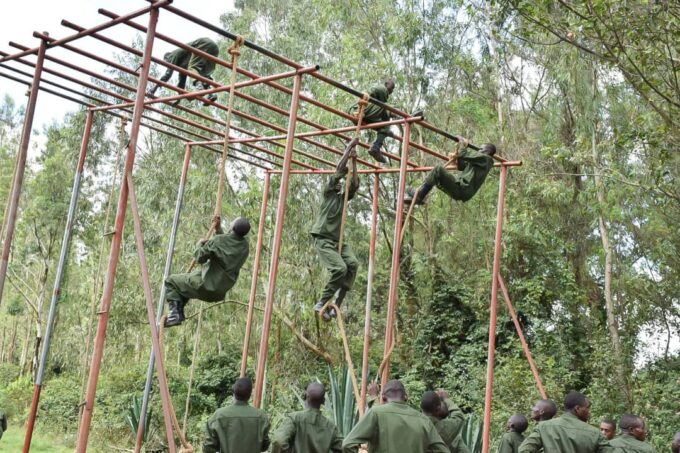

In recent years, the Burundian government has attempted to curb the rise of street children. Since 2024, police have conducted periodic search-and-seizure operations, rounding up more than 300 children and sending them to rehabilitation centers, including one in Mishiha, Cankuzo province.

Despite these measures, many children eventually return to the streets. Those interviewed cited difficult conditions at the centers, including insufficient food. Some reported being jailed or fined up to BIF 50,000.

“We have to give all the money we make from our small businesses,” one child said when asked how they manage to pay the fines.

Attempts to reach police authorities for comment were unsuccessful.

Government officials have increasingly blamed parents for failing to assume their responsibilities.

“We are still trying to raise awareness among people,” said Ildephonse Majambere, spokesperson for the Ministry of National Solidarity, Social Affairs, Human Rights, and Gender. “But imagine someone comes to a state center for help, gets assistance, and then goes back to the streets the next day. These repeated cycles end up looting state resources,” he warned in July.

Child Trafficking to Tanzania

Child rights groups also report troubling cases of cross-border trafficking. According to ONLCT, more than 280 Burundian children were trafficked to Tanzania in 2024 for sexual and economic exploitation. Of these, 130 children were recruited from Burunga province and 151 from Buhumuza—both bordering Tanzania.

“It is truly incomprehensible and unacceptable that Burundian children continue to be recruited and trafficked openly, from inside the country to their destinations, crossing the Burundi–Tanzania border with ease,” the organization said.

ONLCT urged both government institutions and ordinary citizens to intensify efforts against child trafficking and called for increased financial investment in child protection systems.

“No sustainable development is possible without guaranteeing every child a safe, balanced, and rights-respecting environment,” the organization added.

Leave a comment